CAPTURING the MESSAGE of the MOMENT in Ukraine

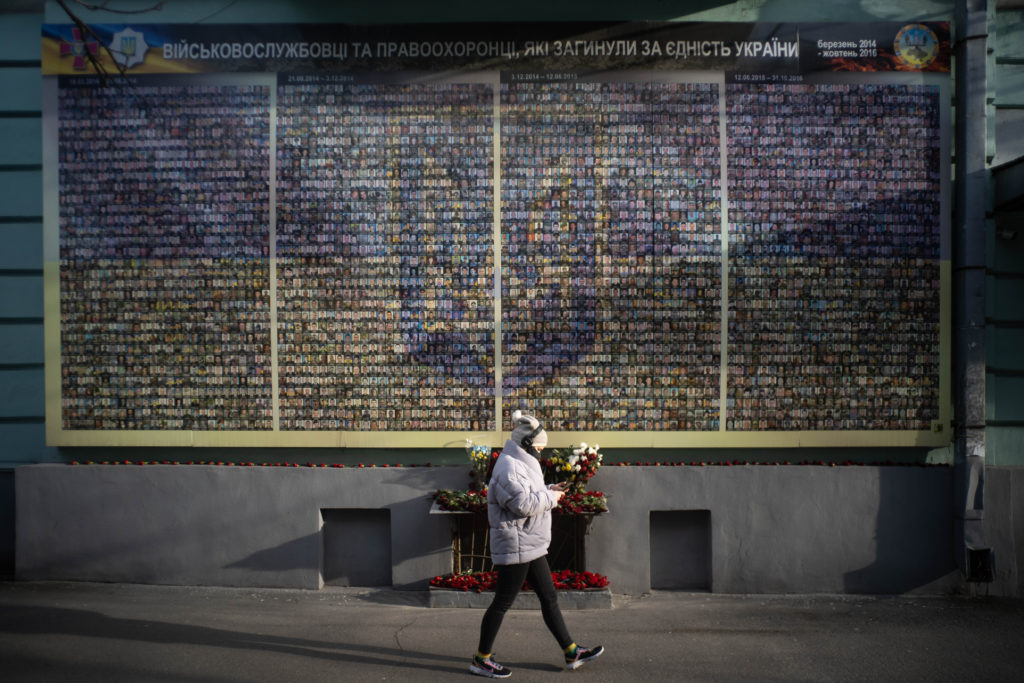

On the 24th of February 2022, Russia launched an invasion of Ukraine. The real invasion however, had started back on the 20th of February in 2014, with the annexation of Crimea. This year sees a full scale invasion, and the whole world is watching closely.

Kaoru Ng was the interpreter for a joint symposium with the Japan Typography Association and Hong Kong Designers Association, held in Tokyo in 2019. I only recently learned that Kaoru was in Ukraine with a simple Facebook post: “I’m in an underground bunker in Kyiv with the air raid sounding outside.” He had flown in from London to do some journalistic work before Ukraine had become a conflict zone, and decided to stay. Coming from Hong Kong, Kaoru speaks fluent Cantonese, Japanese, and English, which he is using to help bring the voices of Ukrainians to various media throughout Asia.

When I got in contact him to ask if we could feature his story in typographics t, he generously offered to let me use any of his photos on the condition it would help spread the word. I also got an interview so I could ask the burning questions in my head; why would he risk his life to go to Ukraine? What are the thoughts of the Ukrainian people? What kind of words and typography does a journalist encounter in a war zone? Kaoru offered his time and energy to help support our association, now is our time to listen to him, and help spread his word.

On Monday the 28th of March 2022, we held a zoom session to a backdrop of incessant explosions in Ukraine.

[Interview, text: Duncan Brotherton (Japanese translation published in typographics t: Akira Uchinokura]

Where are you at the moment?

I’m in central Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine. I’m OK, and things are relatively quiet. The Ukrainians have taken back a few towns both in the East and West of Kyiv. They’re currently fighting the Russians in the North, and I heard they just lost a town and the mayor was kidnapped. The fighting continues; who holds which town changes from time to time. The Russians are falling back so there hasn’t been many missile strikes in Kyiv for the past few days. Last week a huge missile hit a shopping centre 500 meters from here. You probably saw it on the news. That was the last huge attack on Kyiv.

Why did you go to Ukraine?

I was stationed in Minsk (Belarus) two years ago, when the people staged a revolution against Alexander Lukashenko, the country’s president since 1994, and I got to know a few people at the time. In the aftermath of the Belarusian revolution, a lot of people had to leave the country, and many I know came to Kyiv.

I have since moved to the UK, but I’ve been making documentaries on the Hong Kong protests for the Japanese media since 2019. I witnessed many journalists coming into HK in 2019 and reporting what was going on in my country, so I felt it was my turn to repay the international community as a journalist. Ukraine is only a three-hour flight, so I just bought a ticket and came here.

Did you worry about your own safety?

Initially, I didn’t want my plane to get shot down by a Russian jet. When I first came on the 18th of February, the war hadn’t started but tensions were really high, and some airplane companies were cancelling flights. I got in without a problem however. Don’t worry; I’m quite confident I will live to tell my story.

During first days I came in everything was fine and nobody thought that war would be coming to Kyiv. They thought war might start again in the Donbas region, but not here. Those sentiments proved to be wrong.

What kind of work are you doing?

I’m actually a photographer, and I shoot pictures for Japanese media and also Getty Images, but there is so much to do here. Nowadays I record a lot of interviews for TV and participate in livestreams with people in Japan. I also interview historians and professors and ask a lot of deep questions because I’m really into the language, culture and national identity problems here. I haven’t published anything yet; I’m just collecting a lot of information for future writing. To tell the truth it is just too much at times and I feel a little bit exhausted.

What’s the general sentiment of the Ukrainian people?

Before the war started there were about 3.5 million people in Kyiv. There is no offical number, but I think it’s around 2 million at the moment; about half of the city is gone. The trains are still running but they’re pretty much empty. Which means that whoever stays in Kyiv now stays of their own free will. People here are afraid, but they’re not freaking out; they just carry on with their lives. Supermarkets are open, water and electricity are running. The situation is worse in the greater city area. There are a lot Russian occupations outside of the city, and towns have been destroyed. Some places have their electricity cut off, and there is fighting on the street. If people leave their houses they get shot. Those areas are not even that far from here, only 30 min drive.

People growing more and more nervous by the day. Everyone thought the war would be over in a very short time, which is not the case anymore. There is too much fake news and rumours about Russian sabotage and spies being inside the city. The populace is quite jumpy nowadays, especially the territorial defence people.

I see many honourable things. Normal citizens are volunteering, and cooking food for the military and for the elderly. Others deliver from the volunteer kitchens to the people in need. People are rescuing dogs, cats and other pets from the houses where the owner has either left or was killed. There are so many volunteers, and they are well-organised.

How do you navigate the language barrier?

I can read Cyrillic. If you can read it, you can verbalise it; there are a lot of words that are similar to English. I only know about 50 words in Ukrainian, but I have a friend here who is very helpful showing me around. I rely heavily on others.

Could you tell me about your press gear?

It’s very heavy; it weighs about 10kg. The jacket contains iron plates that can stop AK bullets. We were given the gear when we were issued our local press accreditation. They made it very clear that for the accreditation to be valid you have to be wearing all your press gear, including the bulletproof vest and the helmet.

The reception to being press is polarised. Some people are happy to talk to you, some are actively trying to tell you their story, more so outside of the city. In the villages people are less tense, even if their home has been destroyed. For them, the worst is over. The other extreme is people who freak out if they see a camera. These are mainly those who grew up in the soviet era. The soviet government always pushed the idea that journalists (especially Western ones), are all spies.

What kind of words are most important to the Ukrainian people at the moment?

Перемога (peremóha) meaning victory, and Свобода (svoboda), meaning freedom. The most common phrase at the moment is Слава Україні! (Slava Ukraini, or Glory to Ukraine), which has become so common it is the greeting everyone uses now, instead of ‘hi’. You see it gratified everywhere and printed on flags.

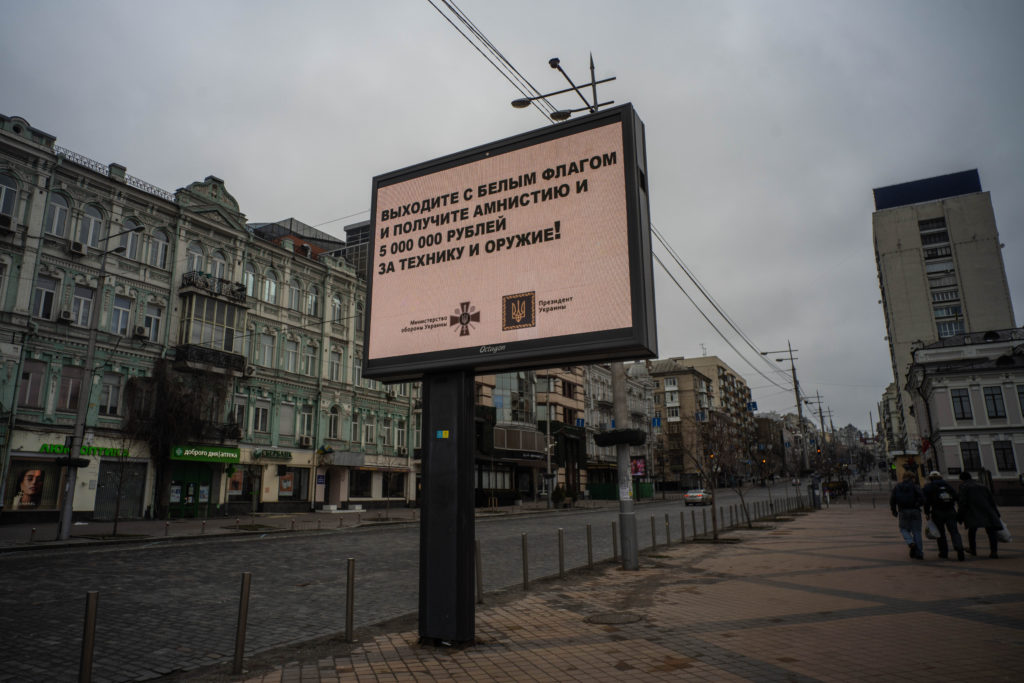

I see an amazing amount of swearing, and curse words. You have probably heard about the now famous Snake Island incident, where a Ukrainian solider said “Russian Warship, go f*ck yourself” over the radio waves. This has been adopted through the whole country. I’ve seen flags, and electronic billboards carrying similar messages. On my phone, I have to use an app for the local carrier, Kyivstar. When it starts, the splash screen carries the exact same message! On the official carrier! It’s unbelievable! Ukrainian digital warfare really has the edge in Ukraine, and there must be a graphic designer somewhere doing this.

A lot of the war-related graffiti has been done at the checkpoints which is a problem, because they’re a strategic location, and we are not really permitted to shoot anything. There are so many lost shots because of this regulation.

As a member of the press, what kind of letters do you look out for?

I know that увагу (uvahu) means attention. I also know the word міна (mina) means landmine. You see a lot of warning signs nowadays because they actually put landmines in the parks. We almost ran into an anti-tank mine on the road in our car. Outside the city, they just randomly put them on the road, and if you’re not careful, you could blow yourself up.

What’s your message to people here in Japan?

There is obviously fake news from both sides. The Ukrainian officials are trying to downplay the damages done to their side of the army. The same goes for Russia. If you jump on social media, there is a strong feeling that Ukraine is going to win, very soon. We have to be sceptical, and not be swayed emotionally by this kind of news. Whenever there is war, there is fake news and information warfare. Just keep a clear mind, but continue to support Ukraine. No matter what Russia says, it is Ukraine that is being invaded.

If an association member wanted to help, what could they do?

The JTA is full of talented designers. Art and design goes a long way with these kind of events. This is officially the first crowd-funded war: a lot of things arriving in Ukraine, including both weapons and humanitarian aid, have been donated by foreign nationals and foreign governments. Design plays a big role here. It has the power to encourage people to support Ukraine, either financially or in person. I believe the international design community has a lot to do.

Kaoru Ng

Graduated from the Imperial College of London in Bioinfomatics. Though choosing an occupation in physics, he became involved in journalism with the democratization movement in Hong Kong in 2019, and started working as a photojournalist. Has held exhibitions of photos from Hong Kong in Japan. In 2020 he stayed in the capital of the Republic of Belarus, Minsk, to cover the democratization movements occurring, which were all too similar to what was happening in Hong Kong. He maintained contact with his Belarusian friends and learned more about the former Soviet Union. At the end of 2021 he moved to London with the worsening conditions surrounding media in Hong Kong. Kaoru flew to Kyiv (Ukraine) on the 18th of February, 2022, days before the war broke.